Note: This is a story that can’t be told in just one blog post but I did my best. Whenever I’m in the beautiful Great Smoky Mountains National Park I think about the people that used to live there and what their lives might have been like. Most people (including myself until recently) don’t realize that the land wasn’t just always empty and waiting for park designation. 85% of the national forest was owned by timber companies, and 15 % of the national forest was owned by small landholders, like you and me. These were quaint, self-sufficient communities….now ghost towns.

When we first moved to Bryson City in June, I started learning about Fontana lake and how when the Fontana dam was built in the 1940s it displaced many small towns in an area known as Hazel Creek. I’ve written about my fear of deep water before….lakes, ponds….ever since my dad told me when I was little about the “town” under the lake we lived on. The Fontana story started to become a little bit of an obsession, especially after one night of sitting and listening to one of the cooks at the inn tell me the story of his father and grandfather, how they lost their land. He told me how his grandfather lost his farm, barn and home, receiving only 4 acres in return. Then he had to rebuild from scratch with no assistance. His father lost his land too….he got nothing in return for it. He was overseas serving his country during WWII and the federal government took his farm using eminent domain. He came home from war to nothing. Stories like this haunt me.

It wasn’t just a few people, hundreds of families were forced to leave their homes with the construction of Fontana Dam because their communities would eventually be submerged as the valleys filled up with water. When the water from the Little Tennessee River rose it also covered roads including Highway 288 which cut off access to the Hazel Creek communities. (here’s the uncovered bridge of 288 when the water level is low). Gravesites below the waterline were moved (although not all of them were actually moved….many Native American gravesites are still there….or if the families couldn’t be reached: graves remained). Gravesites above the waterline were left because the federal government promised the residents who gave up their land for the Fontana Dam that they would soon have a road constructed on the north side of the lake so that they could have access to their family cemeteries. Some families were told by authorities that they’d even be able to return to their land once the road was built so they left sites as if they were coming back…..but most of the remaining buildings were burned leaving only the foundations and fireplaces. You can still see many of these if you hike around the area. A ghost town for sure.

So about that road: despite the promise from the federal government, only about 7 miles of the road that would allow residents to access the old cemeteries and homesites was ever constructed. The tunnel was the last thing constructed and the road project ended there in the early 1970’s due to lack of funding and environmental concerns. (I wrote about visiting the tunnel and Road to Nowhere here.) Now it’s just a creepy tunnel that goes nowhere:

It wasn’t until the 1970’s that the park service began to ferry families over to Hazel Creek a few times a year to re-mound the graves and decorate them. These are known as decoration days. After hearing so many stories I desperately wanted to travel over and visit the cemeteries and “lost” communities. I’d been asking questions about it around town and had gotten to know Helene and Barry, the owners of the Filling Station, and one day when we were ordering Helene slipped Brett a post it note with a name on it and said:

Call this number….this is someone that will take you to the grave decoration.

I felt kind of strange calling someone I’d never met and asking if I could tag along to visit their family gravesides with them. I got a voicemail and left a message: hi, I was wondering if I could tag along when you go to the cemetery next week. The woman that called me back was named Megan. I was surprised to learn that she was only 24 years old….she seemed wise beyond her years. She said I was welcome to come along with her and her grandmother Aileen (“Nan”). She even offered to pick me up and drive me to the cove where they would catch the ferry.

*****

On the morning of the decoration, I met Megan and her grandmother Aileen for the first time. They welcomed me right in. I even began calling Aileen “Nan” and on the thirty minute drive to Cable Cove they both gave me a quick history of the area and answered a gazillion questions I had. Nan’s mother was moved out of a town called Dorsey in 1944. Dorsey is now under the lake. Nan’s grandfather was the postmaster of Dorsey.

We met the ferry at Cable Cove and it took us on a 20 minute ferry ride through a winding route to Hazel Creek, one of the most remote areas of the Great Smoky Mountains:

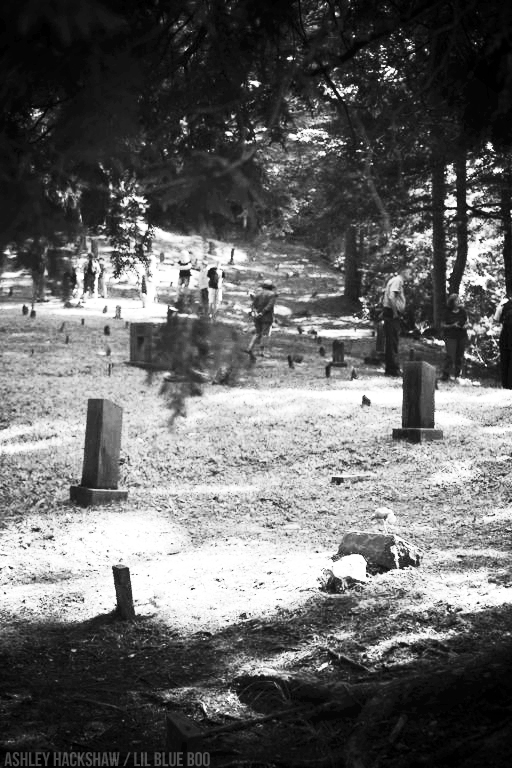

The ferry parked and put a ramp onto the shoreline. We hiked up a steep hill and it opened up into a small clearing where the Proctor cemetery was located. It probably didn’t look anything like this in the 1940s….the trees have grown up around the cemetery, taking over as nature does:

Every single grave was decorated. A few new headstones were put into place to mark graves that were indistinguishable. James Calhoun, a genuine douser, was present to help locate them if necessary.

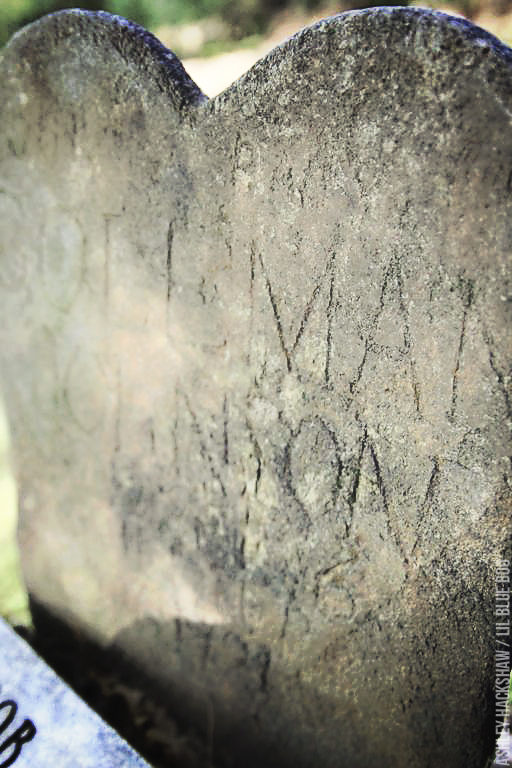

I walked around and read each and every stone. A few of the stones really got to me….like this one that was hand carved into the shape of a heart. It reads “our baby” at the top:

One corner area of the graveyard was primarily infants…most entered and left this world on the same day. Many dates were 1918-1919 and I asked a man what happened in that year. He said that it was the Spanish Influenza.

Many of the grave markers are just stones and others are deteriorating to such a point that the names are unrecognizable. The North Shore Historical Society has been slowly replacing them.

After the decorating of the graves we walked a half mile down a gravel road to the Calhoun house….one of the only structures that was left standing after the residents were forced to move. It was left intact so that it could serve as a bunkhouse for the park service:

The front porch of the Calhoun House:

Here’s a photo I posted on Instagram of the sink inside the house:

This was a bustling little community in the 1920’s. The Southern Railway came in, the Ritter Lumber Company built a large mill, and there was a cafe, a doctor, train depot, school and even a movie theater.